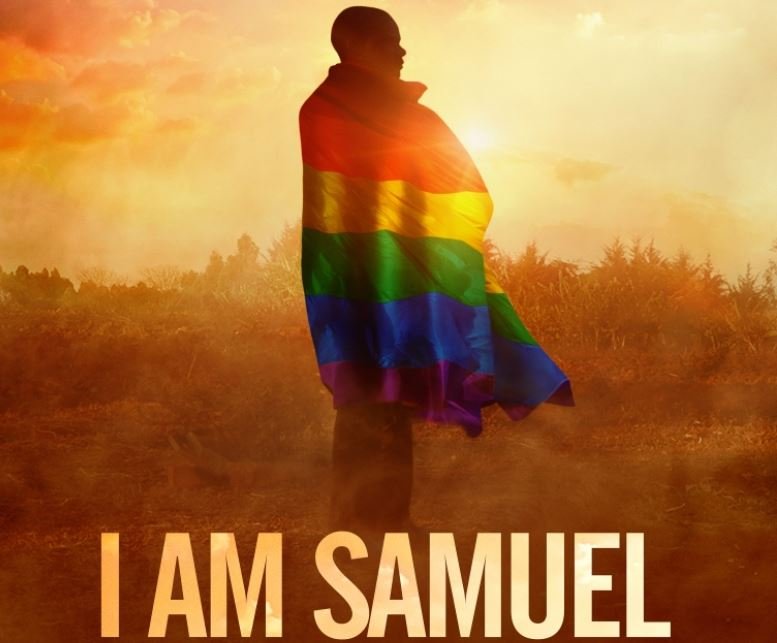

I Am Samuel Review: We Are Samuel

I AM SAMUEL film poster

What’s in a name you ask? Everything. When a person is born, the first gift we give them is a name. They grow up and begin to understand who they are. Society chips in and molds them as the media floods them with images of what they should look like and what they should be. The law descends upon us, clipping away any errant branches, both those rightfully perceived to be crooked and others mischaracterized and distorted into sins and aberrations. I Am Samuel (2020) is a film that puts the power of names and identity into context. When Samuel, a gay Kenyan man who comes out to his conservative family he and his lover must navigate the realities of Kenya’s homophobic landscape. Through the tender eyes of Peter Murimi, we delve into a cinematic world characterised by the duality of hope and fear in the face of indefinite uncertainty.

Despite much aniticipation from Kenyan queer audiences in hopes of viewing the film, the Kenya Film Commission Board (KFCB) banned the screening of the film in Kenya weeks before the film’s premier. This is the same socio-political climate in which the former CEO of the KFCB, Ezekiel Mutua censored Wanuri Kahiu’s Rafiki (2008), citing that its foreign undertones of queer love would incite the ruin of Kenya’s moral fabric. Many local critics of this film, and other films depicting queer relationships, have expressed skepticism towards its celebration of queer life as exporting foreign, Western values into Kenya, ambiguously christened as a God-fearing African nation.

What the banning of I Am Samuel reveals is that the trauma of colonialism deeply dug its claws into the flesh of Kenyan society. Anyone who attempts to shed this skin and reject heteronormativity is quickly reprimanded for being “un-African,” because “that’s not how we do things around here.” These are the ‘gentler’ versions of the violence carried out against queer Africans on a daily basis. Media, be it news or those with massive followings on online social platforms, flood our airwaves and every other channel with heteronormative thought.

In the face of baseless censorship, the documentary desperately provides audiences with queer representation to achieve the director’s hopes of subverting the systematic oppression of queer Kenyans. As we journey through the lives of Sammy and Alex, the intricacies of personhood, faith and family begin to unravel. Through each scene, the film’s ode to love and who is excluded from the perimeters of this humanness all come into focus. Speaking with, Peter Murimi, the film’s director brings resonance to the film’s message: by depicting the beauty of queer love, he hopes the film encourages the Kenyan public to welcome and accommodate the queer love. “I want the film to show Kenyans that being a gay men and being queer is normal. Societal contexts should change to embrace queer existence,” shares Peter. “Through this documentary, we view the life of a man raised in a rural location, working a construction job, just trying to make rent in a non-luxurious neighborhood of Nairobi.” Samuel’s story is quintessentially Kenyan.

They say the best relationship one can have with their parents is long-distance. In these interactions, the roadmap to adulthood and the ambit of parental expectations reverberate. Basking in the dimness of his apartments, Sammy and his inner circle of gay friends converse in the light-speckled shadows. “Our parents know what we are,” Sammy says. They chuckle at how thier parents still dangle the expectation of marrying women over their friends despite their clamorous queerness. Watching this scene animates a relatable pressure every queer African child knows all too well. These uncodified rules our parents imprint on us subconsciously inform every inch of us, including the ways we choose to present ourselves in the world. It’s a consistent push-and-pull between preserving our livelihood to starving off our literally lively-hood, the core of our queerness that makes us who we are. As the crew visits Samuel’s childhood home, his father shows them pictures from his own wedding day, sharing the fond memories and joys of marrying his childhood sweetheart. If love is truly a mirror, what could be purer than Samuel describing his fiancé in the same words and breathy cadence his father uses to describe his mother?

Despite all the film’s strengths, I Am Samuel falls short in its overly optimistic view of religion that borders between optimism and romanticism. For many queer people in Africa, religious institutions like the church shapes our foremost encounter with institutional homophobia. From our tender beginnings, we don these religious hand-me-downs we received from our ancestors to cloak our blasphemy. As Samuel observes the baptism of children from his home village, he reminisces on his younger years when he realized his queerness. At one point in the film, Sammy preaches a sermon in his father’s church with his lover accompanying him. To international audiences, this association might paint an inaccurate picture of tolerance from the Kenyan christian church where our reality is far more grim, harmful and volatile. This aspect of the documentary fails to spotlight the queer people of faith, rejected by their faith communities, who like Samuel continue to say, “I believe in God.”

At the end of the documentary, we are thrust into an introspective scene of Samuel’s rural home in Western Kenya. With the sound of hope colouring the timbre of his voice, Sammy shares that a new name has made an appearance in his family’s routine prayers. The name of his parents echo is Alex, the name of his lover. With this, his parents anoint him with love and finally embrace their son in all his glory.

All around us, hostile homophobic legislation continues to circle at present. To the devastating ruling of 2019 against repealing section homophobic colonial Penal Codes, as well as the 2020 anti-LGBT bill currently tabled before the Ghanaian parliamen., I Am Samuel signals the time to re-examine the guiding forces behind hostility towards queer peopl in Kenya. Sam and Alex are just a bunch of Kenyan guys, arguing over birthday plans, dancing to Kenyan pop in the cramped space of their living room. The idea that love is unnatural when it is shared between two people of the same gender is one that holds no water. I Am Samuel is a story which shines dazzling light that no prejudice can eclipse.

We are Samuel.